I’d received the Tao Te Ching as a gift a few years back and just got around to reading the book this last week. The book often speaks of restraint. This has made me think about how much of my relationship with Gambia to share, keep to myself, sacred, just for me or just for my family there. I wonder if its ever really worth it to try to preserve events, loves and ideas of the past? It’s like a picture of nature, it never really does it justice. But maybe it’s better than nothing and that warrants the effort to preserve and share.

I was watching some old videos I took in Gambia this morning – of family and friends cooking lunch or sitting around talking and brewing attaya (green tea) – and there was a part of me that felt gross about it, ashamed at objectifying other people’s way of life as a topic of interest for me; using their life as a subject that I would explore then leave. Now I did give and reciprocate a lot during my time in Gambia but I think there’s still something like an undercurrent inside me that’s always keeping me a little sad, and keeping me wondering about my family and friends there. After thinking about what that is I guess that it’s some type of compassion; the result of close proximity and involvement with others that prevents me from slapping my hands together and exclaiming “well that’s that, success!” I can’t really say “goodbye and i’m done,” and I can’t fully disconnect from the fate of my friends there for some reason. I catch myself daydreaming often about them and wondering if they’re really happier than us here or if the idea of simplicity and depth of culture is actually a thin cover over the struggles, lack of opportunity, sickness and poverty. Maybe I romanticize their lifestyle to make myself feel better even? I’m still not sure. The videos I watched this morning possibly brought up the fact that our lives were intertwined so tightly for a couple years that we, i don’t know, turned into each other a little and as such I can’t ignore the fact that my family is still there, same as before I arrived, working hard and trying to improve their lives. And because they are there, a part of me is still out there, and I can’t drop them and forget. It may actually be something akin to survivor’s guilt with me wondering “why do I get to live here with comfort, great opportunity and good fortune? Why me instead of them?” In fact, I think that’s it,, and if I’m so fortunate, how am I showing gratitude for the chances I’ve received?”

So my service reminds me of higher academia a bit, in that when you leave you end up having more questions than answers. And that’s what i’m wondering about trying to write this blog post. Questions like, does it cheapen substantial things when you invite others to know it? Has it always been in vain to try get you up to speed and in the know, or is it still part of my service to share this part of my life out with others? Are my expectations unrealistic in thinking that you’d understand and relate with it? Should I just keep answering inquiries about Africa with the joke”Oh it was hot out there!” and get back with the program in the states? Leaving Gambia does feel like a loss and the process something approaching grief and, as most of us know, that is, ultimately, an individual construct to work with. But what was lost really? Skinner wrote that we don’t actually miss a person, place or object in itself but we miss the chances they occasion/allow for us to behave a certain way. So, maybe that’s what I miss; I valued the way I thought, talked and acted in Gambia and to a large extent I can’t behave that way anymore. The people, places and things of the US occasion different behaviors, different values, etc. But you can mix the two, both histories, and I will. So, if Gambia was pure blue and the states pure red I’m now going to see what shade of purple I end up.

It’s been just over a year since I left The Gambia. As I was organizing old pictures I was thinking about doing a final wrap up blog post. This was a little overwhelming because there were like 3400 pictures and equal amount of things I could say that happened. It’s really taken a year to process it all – and i’m not done – it’s been pretty non-stop since leaving – 6 months post-service travel, grandfather’s funeral, relocation back to Hawaii and getting set up farming here. So, to me it seems I’ve not really had big stretches of time to sit and think about what happened. Writing all this definitely helps though. When i do think about it, I just catch myself thinking “wait, what just happened!?” Really, it’s all like a dream to me, a passing memory, an idea that was borne, rippled out into approximations of pragmatism, behavioral theory and “helping” then faded into some kind of feel good service nostalgia. I still find myself thinking and speaking in mandinka, when I walk with my dog I brainstorm ways to give back to my people there. I send them developed 4×6 pictures of what I’m doing now, with some chocolate and tree seeds. I try to show appreciation in quiet moments of gratitude and i’ve found that talking with other returned peace corps volunteers (RPCVs) provides the most comfort and understanding. I feel like I now understand a little bit the solidarity between war vets or any group of people with shared experience. It bonds people and picks your audience. I dropped back into the states and looked around, somewhat desperately, for people like me: other PCVs, development works, people who’d traveled internationally. It was especially skipping off the atmosphere to reintegrate to the states while the elections were happening too. So, to sum it up it kind of went from leaving Gambia and saying in gratitude and awe “what happened there?!” to getting back to the USA and saying somewhat annoyed “What is happening here!?” And then maybe the transitional part to play out “OK, what do I do here?!”

It’s still a work in progress to process all this and balance the two sides but what a good setup for growth and development right? I’m grateful i dont have to sleep under a bug net, take malaria meds daily or ride my bike in 120F weather; nope, i turn on the AC while driving in my car and yell “America is niiiiiicccceeee!” It is. It really is. And the challenges are so much further up maslows hierarchy of needs that i’m playing a whole different game here, with big money & bills, expectations of others being ramped up, family, a tractor instead of donkey, future, wife and kids potential. It’s all heavy and it’s all kinda great, the range of life. I’m excited to see the truths and lessons that transcend contexts. I know they’re there and i’m keeping some as secrets for myself.

As I’ve thought about what I’ve gained from my service in Gambia I see that above all it was the relationships and perspective, which can also just be seen as relationship to self and the world. If i had to sum it up i’d say that there were 5 main relationships borne in Gambia:

- My best friend Modou

- My host mother Fatou

- My welding mentor Ma

- Myself to the land/farm/nature or environment in general

- My wide eyed growing Gambian self coalesced with the ‘self’ I’d built in USA up to the point I entered Gambia (this one’s tricky but stay with me). It’s basically that what I thought I was with my straight A’s, teeth, god and ego gold stars gets completely reevaluated and I had to build an identity and self-worth distinct from most everything I’d narrated to myself thus far. If my pre-gambia ideas and “self” was a comfortable couch i’d been lounging on, Gambia lit the whole thing on fire as I yelled “hey i was sitting there!”

I’ll emphasize the above in the pictures below.

The perspective that changed during my time in Gambia is probably my favorite surprise guest at this point in my life – it’s the way of talking about the world and how I fit into it now that’s so unique and enjoyable to me. It comes down to the language used and ideas thought that lead to the behaviors enacted. The order is something like ‘noticing’ any sights, sounds, smells etc. then the thoughts, language, behaviors that set up long term habits or actions that determine values. What I liked about Peace Corps Gambia is that I got to develop and grow in a relatively safe place, very free with respect to time, social pressure or expectation. It’s essentially like having the whole dance floor or amusement park to yourself – you get to go wild, be weird, form new identities out of your anonymity and can change focus or directions from one day to the next. While this can lead to some anxiety, as there is some comfort in having your path dictated to some extent, being told what to do, when I got past the fear of the great unknown/open/void and saw the opportunity in front of me I felt great! I could kind of make up my world; it was all open to me! It’s that perspective, the music playing in your head, the intangible ideas and outlooks you have when looking at the same cardboard box as 10 other folks and seeing it differently that I most appreciate and i think we should nurture. This advocates for the keep it sacred and secret approach.

So, while I originally thought to keep the blog to the 5 or 10 most profound, earth shattering, mind warping conceptual pictures that will lead to existential breakthrough and “OMG” moments of insight, I actually was thinking that if perspective is the biggest gift I got, then I’m going to put a bunch of pictures up here and say a little something about each one and what it means to me, what I thought or think about it now 3 years later in some instances. So, my summary attempt is actually turning into “my perspective on over one hundred pictures from the west african country Gambia between October 2013 and December 2015.” I will try to keep the captions interesting, in the sense that i’m super honest about any biases, prejudices and wonders I had surrounding the various events (its not gonna be all cleaned up like “PC was an amazing experience that demonstrates the value of cross cultural development and teamwork!”) I think too, since you’ve followed me along my journey then you would appreciate some of the gritty details at this point: i’m all done and i’m safe and I pulled it off really well, so let me tell you some of the stuff you may have wondered about. It was an amazing experience, no doubt, but it was mostly sweat, dirt, challenge, heat, books, catharsis, journal burning, trash burning, skin burning, pounded freshly harvest rice burning, and ‘i can’t believe i did that’ reflection. When I got back to Hawaii my friend said “I thought you would definitely do it and finish it, but I didn’t think you would enjoy it as much.” Neither did I to be honest.

Ok, here it is, my perspective free roll; the wrap up post. I will likely bring Gambia back into the blog for reflection and as a sounding board for my future farm activities, which will be the content of the blog from here on, but for now lets put some pictures up and talk about what happened.

I’d not heard of Gambia until the Peace Corps recruiter sent me the email with my acceptance and welcome letter. Like most PCVs did, I opened up a new internet tab and googled “Gambia” to see where I was headed. I also googled “Gambia surf” and was pleasantly surprised to find that you could surf there. The country was perfect I thought – small and never far from water, either the ocean waves or the river’s fishing. I was so excited to be going to Africa because it was guarantee going to be extremely different than where I was from, I assumed I could help a lot teaching rural folks about natural farming, and I knew that with radical environment shifts comes substantial learning, growth and shifts in perspective. The night I found out I remember driving to Target in Hilo and buying a 6-pack of heineken, a box of lucky charms and the DVD Roots. In hindsight it was kind of a silly attempt to learn about Gambia but I loved the sincere eagerness and attempt (Beer, cereal and Roots – what else could I need!?). From that point on my focus was on Gambia and preparing for the transition out of Hawaii and the US. I honed my natural farming skills, finished my job, downloaded mandinka language mp3s and prepared as best I could for life in Gambia. From Hawaii I’d go back to Michigan and North Carolina to visit family then fly to Gambia.

Too late to turn back now – October 2013 – about 20 “volunteers to be” take the bus from Philadelphia to JFK airport to fly to Belgium then fly to Gambia. Everything new: new friends, new jeans, Teva shoes, gummy bears, argyle luggage marker, fears, Ipod case. Along with the giddy excitement a part of you searches the bus to find other likable balanced individuals that confirm you’ve made a good rational choice. We’re looking around at each other like “this is a good idea right!? Right…..?”

Foreigners are called “toubabs” in Gambia, not insultingly, but descriptively. Here are a bunch of toubabs under a mango tree attending one of the main pre-service training (PST) sessions. One great thing about PC is that you meet such interesting and good people that become your best friends and support systems, to the right Gene is explaining how hot it is and Becca on the left is just happy to be there :). Remember the word “toubab” because i’ll use it often to refer to Caucasian folks, and I’ve grown quite fond of the term. One strategy to avoid the frustration from being called a toubab 100 times a day is to just accept it and start using it yourself.

These are the 2013-2015 Agriculture sector PCVs. We were in country only a few days at this point and took a group picture at our training village Jenoi. As a sector, along with Health and Education PCVs, were called AgFo’s, short for agriculture/forestry or sometimes called dirty AgFo’s, which i always liked, as I think the stereotype for our sector is woodsy, hippie, dirty and free spirit. We’re all looking pretty clean here since we’re new in country. Lower right – that’s our peace corps volunteer leader (PCVL) Seth; he was one of my good friends out there and was a great influence on us trainees. Seth had extended his service and stayed in country well over 3 years before leaving. He was a great person to chat with for perspective, advice or anything and we still stay in touch to this day. They say in Peace Corps you make friends for life and I think that’s true.

In Gambian culture children are named a week after they are born, the newborn’s hair is removed and a name is announced to all in attendance of the naming ceremony. If you’ve seen the children held up toward the stars in the Roots series you’ll remember that naming children and names in general are very significant to Gambian culture. In our naming ceremony they didn’t actually shave all of our hair but we did get Gambian names. My host father gave me my name: Mohammad Gassama. This is the start of the shedding of your old identity, with only about 1% of the people I’d met knowing my real name “Stephen.”

My host father Musa Gassama at the naming ceremony. Musa gave me the name “mohammad” and I took his surname since I was living in his compound (i.e. “kunda). I stayed in Gassama Kunda for about 2 months during my pre-service training.

Attention. In school I had learned that one of the functions of behavior is to get attention. it’s good to get attention right?! Feels good…..in moderation. I had no idea the amount of attention I’d get during my service and how I’d struggle with the flood of it. It was impossible to blend in for me or remain anonymous in any way, everyday was intense in this regard and led to both the indulgence of ego as well as shutting down at times. In the picture above, these folks came to watch the toubabs get their names at the naming ceremony. If you’ve never been looked at like this, imagine it, it’s really shocking actually. As a white male growing up in middle SES Michigan I’ve rarely felt like a minority or that out of place in my life, but Gambia was full on – even the young children get at you and check you out, straight curiosity, no smiles, no polite looking away as we’re taught, they look through you almost and it checks your convictions and serves a reminder that I was the one who went to Gambia, I wasn’t invited or asked by the people there to come over and help us and teach us your ways, it’s not really as romantic as that. It was my idea to go try to help so it’s on me to change and grow because the train of Gambia and its culture is rolling and you better get with it. And to a large extent I don’t ‘belong’ there, it’s true, and you gotta assume you’re the “one of these things is not like the other” thing when you become the focus of so many people. As a side note, this picture makes me appreciate Gambians because they’re really true to themselves and stay with that, not really much playing to the camera, or at least it’s not as automatic in this case.

This is my host family in training village, Dad, mom and two little siblings. Musa is holding my namesake which we called “child Mohammad” and I was “big Mohammad.” One of those great Gambian photos where you can tell photograph culture is not a priority.

LCF – language & culture facilitator. Kunta was my and 3 others LCF and our guide to Mandinka language and Gambian culture. Every weekday for about 5 hours we did language training – the biggest part of our pre-service training. Kunta was a great teacher and good friend to me because I could really ask him anything and get real about touchy issues surrounding development work and culture.

With no plumbing or running water near the houses we collected from a well or pump. That makes your shower and your washing machine the same thing: a bucket. It was transported 20L at a time in older oil jugs called bidongs (the yellow jug on the right). A lot of life involves bidongs, they’re kinda like the go to transport system. The rice bag also. Traditionally collecting water was a woman’s job and i definitely got a few looks and laughs trying to carry my own.

As one of our training assignments we AgFo folks had to double dig a garden bed and sow vegetable seeds. This was my backyard in my training village house.

Put the 4 drops of bleach in the liter of water and drink the water. Repeat for duration of your service. Compliance? Umm, partial. One way you can tell how new PCVs are in country is by how clean their nalgenes, shoes, clothes and bodies are. When the new volunteers would arrive from the states us older PCVs would pull each other aside and laugh “look how clean and new they look!”

This is the street in front of my training house. Look at the fence on the right and the brick wall on the left. Why this road is important is because there’s no cars so people walk by all day and that simple act stitches you into a communal lifestyle. Coming from an individualistic society this was a big change.

“America” is where us toubabs are from. The USA is impossibly big to really understand when Gambia is around 15-30 miles tall and 290 miles long. I showed my people where I grew up in Michigan, showed them where I lived in Hawaii and then they asked me if i’d ever seen Obama and where does he live! Obama is pretty much a pop hero in Gambia, there’s even an “Obama” brand of pens sold as most shops.

I did miss Hawaii, surfing, my friends there, my dog, the rain and I thought a lot about it. I didn’t know it at the time of leaving but my time in Hawaii and the bits of attitude, culture and perspective I picked up there would really help me in Gambia. I think because Hawaii is more country living, people first and small town communal lifestyle. I was also somewhat of a foreigner there so I had to stay humble, listen and base relationships on trust, which was exactly what happened in Gambia. My language teacher Kunta would always greet me with a hug and an “aloha bro!”

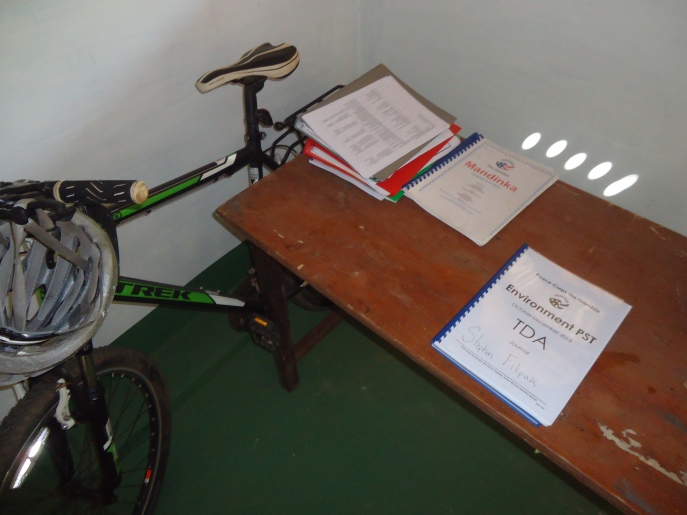

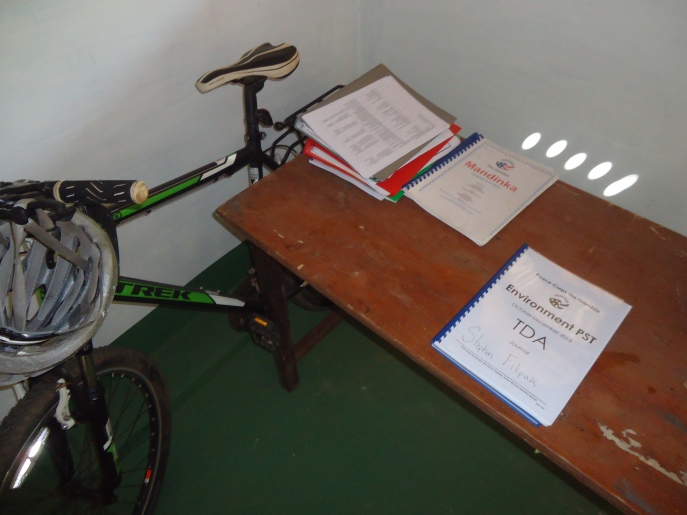

As a PCV you get a new trek bicycle, helmet mandatory. You get a language manual (for me Mandinka) and a book of daily activities you should do while in training (e.g., go to the shop and negotiate the price on food, take local transport to the market, go talk to your tailor about clothing). Gambia PCVs used to be able to drive motorbikes but it was determined to be too dangerous. Still, some PCVs break the rules, riding motorcycles or their bikes into other countries! It’s not that difficult to ride out of Gambia because it’s so small.

There were 8 Mandinka speaking volunteers in my training village (called Kiang Kaiaf) and sometimes we would meet up to practice language together. One interesting cultural thing about Gambia is that when guests arrive you will quickly put chairs out for them. Nobody really sits inside during the day so it’s chairs and maybe water, you always try to give your guest a seat. In the states there’s usually set couches and chairs that don’t move, in Gambia it’s good that their portable so you can follow the shade under trees and roofs as the days passes. These are some of my mandinka training friends, all of whom made it through 2 years and 2 months, finishing the full service.

Throughout training the PC team try to figure out what volunteer will be placed at what site. Everybody wonders where they will end up for two years and the PC training team try to do interviews and get to know you to determine if you’d like a big city, rural setting, would be OK riding your bike long distances or would prefer a small family in a small setting etc. All the trainees wonder where we will end up and finally the day comes when we’re all marched blindfolded to a giant map of Gambia drawn on the floor. The PC training team then places you on the part of the map that corresponds with your permanent site. Then you count 1,2,3 and take the blindfolds off to reveal where you will be living and who will be near you! Sometimes the friends you made during those first 2 months of training stay close and sometimes you see them get placed way out in the bush! I remember a PCV joking to a friend that was placed way out in the boonies “well, see in a couple years!”

After two months of intensive language and cultural training you attend a swear-in ceremony at the US ambassador’s house and officially become a peace corps volunteer, as opposed to a peace corps trainee. You then can excitedly tell your people in the states to change your address from PCT to PCV! The swear-in ceremony is broadcast over Gambian television networks and you get a certificate with your name on it, perhaps a picture with your PC country director Leon, and then you have a party night with the other PCVs then move out to your permanent site within a day or two. For me there was a big sense of accomplishment at this point, I was thinking “OK, i’m an official PCV, let me get at these 2 years now! Put me in the main event and let me see how I do!”

This is Gambia. Situated completely inside of Senegal. The capital is Banjul and you can see where my site was, half way upcountry on the north bank of the river – Farafenni is the name of the town. The name comes from the fact that the town was started on the corner, or tail end, of a large rice field; in Mandinka “faro” is rice field and “fennye” is tail, so my town, Farofennye/Farafenni, is the corner/tail of the rice field. Some people joked that it was called Falofenni: donkey’s tail. There’s a little deeper story too if you want to know, the nickname of Farafenni is Chaku Bantang. This is because the wife of the founder of the town was named Chaku, and she planted a silk cotton tree (md: bantango) at the first compound built in town. So they called the tree and town “Chaku’s silk cotton” or “Chaku Bantang.” The founder of the town was a mandinka man named Wally Diba as far as I understand and it was interesting to know that my house was in the Mandinka section of the town, one of the oldest parts, and just a few hundred feet from where the original silk cotton tree was planted. My host mother’s surname was also Diba, so I felt I was in a special town, in a special part of that town, with special people. This all made me realize that the names of places and people carry on their stories.

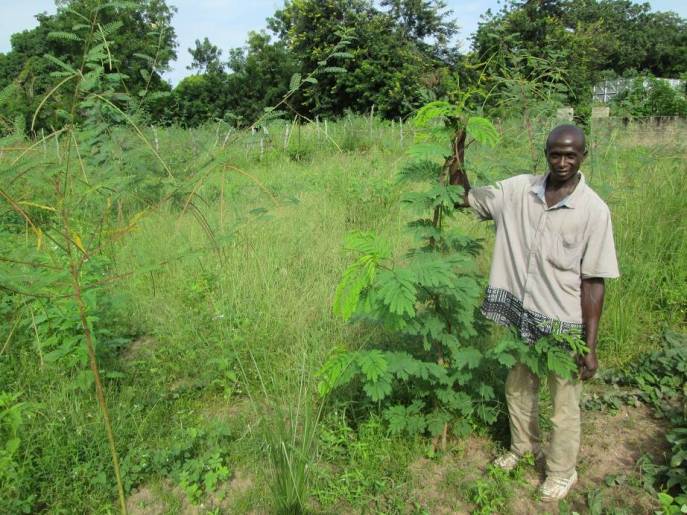

“Site visit.” This is where you go visit your official site for the first time, you see the place where you will be for 2 years. Here my counterpart Momodou shows me around the farm. It’s kind of a mix of all sensors activated to predict how you’ll do for the next 24 months and it comes out a split of “o wow!” and “o sh**!” My site had huge potential with respect to farming. All of the land in this picture was available for projects and there were already bees under that big tree on the left.

Here are the bees. I was happy to see that the school was already keeping bees. The apiary was under a huge African mahogany tree (khaya senegalensis). As service went on my counterpart and I were invited to beekeeping workshops, caught more bees and built more hives, at one point having 5 colonized hives under this tree. Once somebody even stole one of our hives – we suspected it was the bakers that use the hive boxes for mixing large amounts of dough for bread! Gotta watch those bakers! Actually it was our fault for assuming that nobody would take an uncolonized box, and what we learned is that when there are bees in the box they act as their own security and prevent theft. Still, we planned to do a mission to visit all the bakers in town, buying bread, and scoping out their shops for out beehive. We never found it though!

Bees in one of our new Kenyan Top Bar hives (KTBs). Hmm when I look at this picture I see that the less involved you are with something the more you can romanticize about it. Upon first glance and interaction bees seem great! They are for sure, but when you get more involved with them and they light you up a few times it’s another story. African bees are no joke in terms of aggression, noise, etc. I got worked over so hard in Gambia, and these bees don’t let you get away with anything – like I tried to do a quick job in my sneakers, with pants tucked in my socks and I got worked! Within 3 minutes i had been stung about 14 times on my ankles, through my socks, and my feet were going numb as i was 7 feet up on a ladder in a cashew tree. I made it down safe, job incomplete, but I was sure humbled. African bees are legit!

Gambia has an Atlantic coast and faces the east coast of the US. Here the sun sets in the west and we look for surf. At times there was waves and I could help people learn how to surf. The real trick was to head north to Dakar, Senegal and surf some serious waves! Just 10 hours away was Dakar and a whole different scene. Our peace corps house in the capital was a 10 minute walk from the beach so we’d have plenty of days at the beach. The peace corps house, the transit house we called it, was such a relief to visit because it had AC, couches, a big television and DVD player, hot showers and was close to shops and restaurants. It was also a blast anytime you got to spend time with other PCVs.

This is my best friend Modou taking me through the bush to go throw net for fish. He’s such a classic to me – classic good guy, classic African, father, provider, farmer, bushman, hunter, fisherman, handyman, friend and support. He’s done so much: was a taxi driver in Gambia’s capital, a fisherman on the river for 10 years, a farmer his whole life and I am so grateful he took me under his wing and decided to be my friend. I was such a dork out there in Gambia and he stuck with me for my whole service! I couldn’t do anything, like a baby out there for so long and I was so obviously an outsider but just about every day we hung out and he never seemed to be embarrassed or ashamed of cruising with me on bikes through the streets or inviting me to a party of his family etc.. He taught me so much just by being himself. I can’t say enough about him but I will put little gems of wisdom here and there in attempt to introduce him to you. I’ll be talking about modou for the rest of my life, I’m sure of that.

Modou puts a reed into a ball of corn flour. When the fish bite it the reed shakes and then he throws the weighted net on top of the reed to catch the fish. We caught tilapia here.

This is a tributary that leads to the large river Gambia; the river that cuts through the center of the country. Modou became my hero in a lot of ways. He always taught me African proverbs and never asked me for anything, not once in 2 years did he ever ask for a thing, it was amazing especially because he deserved a lot and, if you don’t know, you get asked for things all the time, as a toubab, people ask you to marry them, to help get them to America, for your bike, for your Nalgene bottle, for you to introduce them to a toubab wife, for your pen, for candy etc. It’s not a bad thing, it’s what happens when most people have just about nothing and they see a toubab stroll by, but for Modou to skip all that for such a long time was really special and demonstrated his character and humility. And we just hung out all the time, working in the garden in the morning and watching 80’s chuck norris films like Delta Force over dinner and attaya at night. One thing Modou would always do is to ‘push you out’ in that he would walk with you a little bit when you left his compound, maybe to the street or to the corner of the block, always saying “thank you mohammad.”

My sister Stephanie in the states had started the welding/metal fab tradition among us siblings and I kept it going in Gambia at a local welding shop. This art ring was a gift to her to say thanks for the inspiration. Why is this little art piece more important than it seems? – because hobbies and varied activities were the key to a balanced service; for me I had to keep multiple irons in the fire because likely one is melting or blowing up or not iron or actually made of rice! In other words, it was bad to monocrop your identity or role as a PCV because it leads to a system less resilient and that’s not a good thing in the wild world of 3rd world development work. For example, if a mother instructed gang of 5 year olds stole all the cashews at the farm I could say “screw this stupid farm” and go laugh and weld with the guys at the shop, and then go to the farm the next day. Having many hobbies helped you ride out the bad times in one area of your life.

Any guesses? Do you guys remember this one from my earlier blog? Cultural agriculture traditions were some of my favorite things to talk with people about. I was taught by a Mandinka farmer named Saikou in Jenoi and my Jolla counterpart Momodou that for the luck of your farm you will bury the above items in your field. The slippers are good luck because they get away with stepping on everything but nothing ever steps on them. The garlic, salt and hot pepper are to sting the mouths of people passing by and cursing your farm and therefore protect it from ill will. Another tradition is to start serious farm work on a tuesday! I hope to carry on some of these traditions as I continue to farm.

Stay open to all things – animals, ideas, people, experiences etc. That was the mantra.

I just think – “what has eight legs and is powered by a whip?” A tractor in Gambia. Plowing the fields for my first real attempt at farming – Gambia, August 2014. This is one of those pictures that turned out really good. Modou is manning the whip in this picture. It’s true that donkey’s do get to a point where no matter how hard you whip them they just kinda give up, call it stubborn or just plain exhaustion and helplessness. I think I whipped the donkey a couple times and modou fired me from the job because I didn’t do it hard enough.

The farm crew, first rainy season – 2014. See what I’m saying about one of these things is not like the other!? Yea, no chance to blend in, this picture says it all, ha and my beard is pretty ridiculous. Anyways, the secret thing to these guys is that i’d ask them huge life questions and they always gave great answers. I asked them “should i live in the states and farm?” and they would say things like “Yes, we need more farmers, and less talk talk talk. People like to talk, they don’t like to work. Working hard is good.” And i’m thinking “well, that’s that!” 🙂 Their perspectives were refreshingly uncomplicated, especially as my service came to a close, we brainstormed what to do with my life together and they provided a lot of kind gentle support, never preachy or unsolicited.

When you want to build a fence upcountry you’re given a machete and sent out to the bush to cut fence posts. These are neem tree branches and shouldn’t be consumed quickly by the termites due to their bitterness. Building this fence was one of the toughest jobs I did in Gambia – 153 upright posts all cut by machete up in trees from 10-35ft in the air. I guess it is risking your life for a fence, but in Gambia it’s pretty normal so it doesn’t stick out the way it would is the states. I remember listening to a lot of incubus during this fence work, and I could do 15-25 posts a day until my hands were totally numb from digging.

You need a fence to keep the goats, pigs, and cows out of your farm. And it must be made well in advance of the rains so you have to rush to construct it and dig in very dry and sandy dirt. My first farm here was about 1/3 acre. I’m just really grateful that I had the space and a few helpers available to me for building this fence. The school gave me permission to make this farm and I couldn’t have done it without the guys help, it was just too much work for one man really. When I was putting this fence together I made a promise that I would never complain about putting up a fence with wire and t-posts in the states :). Pounding the first two feet of a fresh green t-post into soil? What a dream!

I learned the term “broilers” when we bought 300 chickens to raise and sell for meat. The real truth behind this photo is that it was a manic race to sell all the birds before we ran out of food to feed them. So we cut the price of the birds to push them quicker, pounded are own millet to supplement the dwindling feed, and even rolled them around town in a wheelbarrow trying to sell them. “Hey, guy, how about a chicken for dinner tonight!?” Timing is everything and we didn’t really pull this one off successfully. I had a mentor at SIU named BFG and his words were ringing in my ear at this moment: “it’s the implementation of the idea where you fail or succeed!” Everyone loves a good emotional high sitting around the table (“yea lets do chickens! it’ll be great!”) but grinding it out, especially with these birds, was a real drag and we definitely blew it.

This chicken was brought home to my host mother as a gift. I walked home from the school, about a mile walk, not too far, but carrying the chicken made it strange and most people gave me smiles and waves or made a passing comment about how they were coming over for dinner! Sidepoint: it may be hard to tell because i’m usually tall and thin but in this picture I am about 28lbs lighter than when i first came into country. I felt like the chicken – very stringy and lean.

It seems all over the world there are tendencies for the light skinned to want to be a little darker and the dark skinned want to be a little lighter. In Gambia, the younger women would buy products like this and straighten hair etc. to get that euro toubab look. There’s a lot that could be said about this but it’s a jump off point for an in person conversation perhaps. I will say that all over the world people struggle with self acceptance; it cuts across race, location, SES and age.

My service site and farm were at a high school so I was able to teach classes about agriculture occasionally. Does anything stick out to you about this picture?

I feel grateful that friends and family spent time with me, helped me practice language, took me ceremonies and helped me navigate the country or simple community event. I have to chalk it up to the fact that there’s less ego out there; I mean if you were egotistical and going to a party where everyone looked, acted and thought like my host brother here on the right would you really wanna take the guy on the left? Ha, i say no way! And ya know I would’ve really blended in had it not been for the Levis! yeah right :). I felt really welcomed and accepted in Gambia and people made a lot of effort to include me in their culture.

The infamous “gele gele” – public transport in its most disturbing incarnation! Ask any 3rd world PCV about public transport and guarantee they’ll laugh and have a great story. Put a cow in the gele gele, a ram on the roof, pay off the cops to let you pass, a leaky basket of fish, whole axles falling off, 28 people inside, boy with broken tibia transported to a medicine man in the bush……o yes it all happens on the gele gele.

When you get the front seat in the gele gele you’re really feeling great! It feels like an african safari or like you’re in a motorcycle diaries type movie. If it’s a hot day the air feels like a blow drier pointed at your face but you take pleasure in the simple act of going for a ride. One important change that happened in Gambia is that my standards really changed. It really took less to make me happy and I found enjoyment in such simple small things or experiences. A cold coke, dunking your head in a tub of water, or taking shotgun in a rumbling diesel van without a seatbelt all are fun, simple as that. It’s like the quality of the experience really amplified out there because you were IN the environment, 100% in it, as opposed to more isolated from it or just skimming along the surface attempting to dodge the uncomfortable parts like had become a habit of mine in the states. In Gambia the uncomfortable was unavoidable and that shifted the baseline such that a cold coke or electric fan, for example, was a large and extremely pleasant change in the situation.

Hygiene is strange. Really I think the PC approach for toubabs is to carpet bomb your whole body with strong chemicals, both inside and out, in an attempt to prevent serious illness. It’s recommended to put 4 drops of bleach in each liter of water you drink, you take malaria meds for 2 years 2 months, and then super strong final cleaning detox meds when you finish service along with fecal and aids test to make sure you’re clean to depart. We’re all given a PC medical kit with things like oral rehydration salts for diarrhea, ciprofloxacin for antibiotics, pre-natal vitamins and a whole bunch of other stuff to try keep healthy out there. “Santex” was the go to daily defense and desperate effort to stop heat rash. Still, it seems no matter what I tried I’d still end up sick once every 3 months for about 4-5 days. So what happens when you’re sick? One different cultural thing is that in Gambia the sick are not left alone, but frequently checked on and seen by the family, and this was frustrating for PCVs who feel horrible and just want to be left alone, as opposed to visited by the village elder and told to “come, get up and greet the Alkaloo!” Ha, don’t you just want company all day when you feel like you’re dying, dripping in sweat and can’t move!? The highest fever I got in Gambia was 104.1 if I remember correctly and there was this one time where I swear I was hallucinating riding my bike home, like I was in an alternate universe, because I was coming down with some sickness. I remember having a really trippy chat with the local dentist/gynecologist (yes, it’s the same guy) and laughing because it felt so much like I was in a dream and extremely slap happy.

Gambians really do like PCVs! Even naming their restaurants after them in this case :). This is Omar’s place and a favorite amongst PCVs, located in the captial of Banjul, a short walk from both peace corps office and transit house. Omar is an old time favorite and an extremely nice guy who makes really great food. Sidepoint: One of the things that happens to PCVs is that you start seeing everything “in country” as normal and regular no matter how bizarre or novel, like how this restaurant looks for example. It doesn’t really stick out, but you do a double take and you can’t help but laugh and be like “wait, what!? That’s the restaurant?”

BE WEIRD and DO YOU! It’s OK! This was one of the best things about anonymity and living in Gambia – you can really do pretty much whatever you want and avoid a lot of the inescapable judgement and criticism that makes it hard to do the same in the US. In fact, it’s likely that you’ll catch a lot of compliments for your new style of talk, dress, dance, acting etc. It takes some testing of the water but after a while you get to stretch those muscles and let your freak flag fly if ya want to! PCVs shave their heads, or don’t shave at all, get traditional tattoos, take on new identities, stay and get married, retreat from life and read all the time, become a farmer, drive donkey carts, or anything you want! To explain this, I was told by another PCV that we already stick out so much and people think we’re a bit crazy for coming all the way out there so you can just abandon full integration and enjoy the opportunity to not conform. And while I didn’t get too wild or different, for me and my norms I did push the envelope in a lot of ways. For example, in the photo above I am a white guy in Africa, with a huge beard, huge mullet, orange dyed finger tips, eating an old tuna sandwich, drinking Nescafe under a mango tree: unusual and wonderful! And that’s just the morning, who knows what other situations I’d get myself into this day. You would also catch a lot of compliments for the new things you tried. It was a big relief actually, you can skip the showers and shaving and just relax with all that pressure of how to look and act “right” or “normal.” I imagine it was even a bigger relief for female PCVs, and when you hung out together it was likely that both guys and gals were so dirty, sick, tired, hot, intrigued and confused that you just felt great because you were totally on the same page and vulnerable with them so there was a great sense of commradery and very little shame or affectation.

Modou helps me pound grain in a small mortar and pestle, which is the like the mainstay kitchen tool in Gambia. We pounded some sprouted sorghum grain this time.

Modou poses for a pic on my first animal killing day (I owe modou a lot too for always posing for all my pictures; he never refused and I developed a lot of them for him to keep before I left). We killed our fair share of chickens at the school; in gambia the animals are killed with a knife to the throat, or machete in the case of bigger animals like a cow. The guys even let me kill one and taught me how to carve it up. I believe that according to Islam I’m not supposed to kill animals that we will eat because i’m not muslim but another person said that it was ok as long as I said the correct prayer before doing so. That’s momodou bah, our school shepherd, in the background. While modou was mandinka, like me, momodou bah is a Fula and that tribe is known for being shepherds of cattle. They’re also the tribe to go talk to if you need some milk.

One of the goals of Peace Corps is to share US culture with host country nationals (HCNs) as well as share host country culture with people in the US. It doesn’t have to be anything complex though, perhaps the name of your mother as in the picture above. Little did my mom know but on this day, 3000 miles or so away, there were four guys sitting under a mahogany tree trying to pronounce her name; something like “saaaan jjjrah.” This blog also helps me share Gambian culture with my people in the states.

“Food bowl.” Boom! This is a wonderful foodbowl by the way, about as good as they get! See all the fish and veg, and green leaf sauce? Super good one here. In Gambia you eat sitting or crouched around the foodbowl on the floor, coming together with your people to share a meal. A lot of times people will remove the cover of the foodbowl and say “bissmillah” then start eating. Most use their hands, I used a spoon, and you stay in your section of the bowl for the most part. If you’re in good with your host mother, or are an older male, people may break apart the vegetables and fish and throw them in your section of the bowl. I always liked that little part of eating together, being taken care of and helped without any words exchanged. Portion control is a difficult because you have a huge amount of food in front of you with no clear end point!

Here is a more simple foodbowl so you can see the range as compared to above. This is a nice seasoned rice with fish and hibiscus leaf sauce. I remember reading fukuoka and he said that we’ve lost the ability to enjoy simple flavors: grains, plain tea, etc. 1st point: as foodbowls wore out you just hoped the pain wouldn’t chip off in the food. 2nd: look at the toubab spoon on the right! I rarely ate with my hand.

One little cultural thing that happened was that if you had a guest, like I was here at Modou’s compound, Gambians would serve them a separate food bowl just for themselves. I’m not sure why this happened, I asked Modou and he said it’s just to make sure they’re comfortable and so they don’t have to eat with so many people. Modou would always have me sit in a separate room and his wife would bring me this little bowl with my own individual serving. But then we’d call out to each other to “come eat lunch” and they’d call back to me “come eat lunch here.” Calling people over to eat is an important cultural thing in Gambia and it happens all the time. Gambians want you to eat with them and even if you just left one food bowl they will call you over to another one, stating “hey you didn’t eat, come eat lunch, eat more!”

This is my host mother Fatou teaching me how to pound grains in the mortar and pestle. We pounded a lot of grain in the compound and it was always a fun day when me, the toubab man, would pound. “Mohammad be turo la” the kids of the compound would say, or “Mohammad is pounding.” Often someone may be passing the compound on the street out front and upon looking in and seeing me pounding grain, a traditionally female job, would yell out “hey!” or “good work!” or just stop and look for a bit then laugh a bit and walk on. Everybody would want to help me pound, especially the my little sisters and we would count numbers, 1, 2, 3…etc. alternating english and mandinka. So a few words about Fatou, she’s another really special person to me, my Gambian host mother and an inspiration to me in her kindness and strength, the prototypical matriarch in the compound. Fatou and I would talk most nights after dinner, just her and I, maybe just for a few minutes but she always held that space for me and we really bonded in moments like those.

At the school one day our resident Nigerian preacher brings an owl he caught into the garden to show the farmers. This just sounds like a sufjan stevens song title to me! There’s always something interesting happening and sometimes it comes to you. Owls symbolize transition between life and death and I took an owl feather back to the states without knowing that it would come into play the last time I saw my grandfather.

A large part of Gambia that goes unnoticed is the open spaces, the empty majority of the landscape, “the bush” as it was called, or “wulo kono” in mandinka. I was told by my host family that the bush is not safe, there’s hyenas and monkeys that can attack you, as well as devils and spirits. I think living in a large town overshadowed the fact that Gambia was actually pretty calm and quiet once you got past the outskirts of the town. I liked this part of Gambia because you could walk for an hour and only see a friendly passerby waving from a distance, other than that you were alone with the trees and sound of the birds.

As our first rainy season approached we Ag PCVs had to learn how to farm, Gambia style. This picture shows a few Gambians training the agriculture PCVs on how to run a seeder. Gambia style trainings were so relaxed and efficien – lay out a prayer mat for the PCVs to sit on, get a knowledgeable farmer up there to explain how the seeder works and then go out to the field to practice sowing seeds. No pamphlets, no PowerPoint and then we go play volleyball. It’s a good way to do things and reminds me that effective teaching can be done quickly with few words. The laid back attitude and openness of our training team unified us; there was no large distinction between PCVs and staff, at least you didn’t feel it, and we all seemed like a big group of friends working together. Shout out to Bah2, kneeling down by the seeder, for being such a great teacher and friend to all of us. Bah2 had great one liners like, “O, me I am very powerful!” 🙂

Older sister gives little brother a bath.

I was lucky to find Noni in my town and put it in an old mayo jar.

Noni getting funky in an old mayo jar.

Noni tinctures. I used the Noni fruit to make various tinctures using vodka and brandy. There were many ways in which my time in Hawaii came into play and had a positive influence on my service and recognizing and using Noni was one of them. We used the mango, apple, noni and vodka tincture to help with colds.

If you’re a toubab, they will come! Kids are everywhere in Gambia and they will find you! The great thing is that if you are in a playful mood or want to joke around these kids are definitely game for that. In Gambia you can make a game out of anything with kids and they’ll hang out with you all day. If you want privacy though you better go further into the bush to try escape! Most kids will pose or throw some kind of “cool dude” hand sign. Also, you’ll get touched alot if you’re a toubab, like check out the kid on the far right, taken advantage of my moment of stillness to cop a feel of my arm! Ha, get off me ya little monsters!

Most PCVs read A LOT of books! Books get traded around, favorites are picked, authors discussed and book lists are compiled. Some PCVs had read around 80 books in their first year of service! During my time I read about 56 and I thought I was cooking but some others doubled that; how could you not end up a little smarter or interesting after all that reading time!? Some of my favorites included: Animal Speak, Desert Solitaire, Dune, Pablo Neruda, The templars, two kings and a Pope, and Autobiography of a Yogi. The worst book i slogged through was a 750pg bomb on christian prophets! I’m not saying it was bad in itself but this one was definitely handed to me by a preacher and taken on more as a challenge than a leisurely pursuit. I never stopped reading a book and I’d never skip ahead, always finishing the one i started before going onto the next. That’s the style I developed in Gambia. I’m also still having to catch up on some PC books I didn’t get to, like David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest and the seemingly impossibly boring to finish Guns, germs and steel. I will beat you GG&S!

Honey was called “liyo” in mandinka and was a hot product to have in the streets of Farafenni. The good thing about being the beekeepers was that we could always get first pick of the harvest and help out our friends and our people before the public release so to speak. So, it’s good to know the name of your farmer, it’s good to be friends with the blue collar folks and its good to stay in the dirt with the people that are really keeping the wheels greased and things working. It’s like the movie Titanic, the best times are had down in the steerage deck with common folks, not up top with cigars, brandy and stuffy suits. Being on the grassroots level was a big focus of my service; i didnt’ want to be in the meetings with the principal, playing the part of the smiling token toubab, i wanted to be with my friend modou at the farm, in the heat, dirty and laughing, climbing up trees to shake branches and get mangoes. I wanted to get deep in my community, stay at site, and forego involvement with a lot of the PC events and committees, which can lead one to get the label “site rat.” After a while you see which PCVs are a site rats, in that you don’t see them unless you go to their site :).

Honey. It was always a great day at the farm when we were processing honey. One funny, seemingly unimportant, item here is the spatula, brought back from a trip to the states, and a game changer in regards to scraping all the honey out of the containers. It’s just really funny when I, tommy toubab, come back from the states and introduce the super simple but game changing spatula to up country beekeepers. I can just hear modou saying in Gambian style english “HEYYY! i must get me one of these spatulas, it’s very nice!” And you know I hooked them up with some spatulas!

If i ever write a book about Gambia I swear I’m going to call it “Toubab tries to plant avocado upcountry.” Ha, here’s another avo in the frying pan! If ya dont know, “up country” in Gambia is eastward, inland, away from the atlantic and cool conditions. So the further upcountry you go the hotter it is and avocado are notoriously tricky to nurse through the upcountry heat; you either underwater and they fry or then overwater and soggify their roots. Despite all our efforts and fancy outplant holes, none of them made it. When I left we had 3 grafted avos in the nursery that we never ouplanted, letting them grow through their pots right into the ground where they stood, under the shade, and I think these may have made it but i’ll have to go back and see!

Teaching my counterpart momodou and best friend modou how to graft mango. This was the kind of “development work” that I liked: a simple skill taught in 15 minutes that will have a huge positive impact on their future and can even be passed down to their children and grandchildren: it’ll help everyone come up. Gambians rock because you show them one thing and they really run with it! A week later modou had 60 mango seedlings in the nursery and he said “i’m going to graft them all and have a big orchard!” Right on.

Welding fail: this rake broke within the first 30 seconds of using it. I failed my welding mentor Ma! One thing i did learn about myself, as made clear by my shoddy welding and this rake, is that if i don’t react in the normal “still/silent/disbelief/look down at the ground” route I’m actually a “thrower” in that when something doesn’t work or breaks or I get really angry I’ll chuck it – I’ve found that I’ll either go for max distance out into the bush, or if a wall is near i’ll try to obliterate it against the hard concrete. Anyone else……? -crickets- or “yea man me too!” 🙂

Luckily the school I was placed at had a huge fenced in garden. I was given free reign to do whatever i want here and it became a fun and weird agriculture lab to try anything for 2 years. No rules, no set time, no real demands and a couple guys that would help me with labor and any crazy idea i had. Really, it was the best set up I could ever ask for. I think I really cut my teeth in the peace corps in regard to farming and especially in this garden – learning to machete, double dig garden beds, fetch water, sow seeds, flip compost, prune, manage the nursery, endlessly gather cow manure and wheelbarrow it, companion plant, etc. Shout out to my people in Hawaii that I stayed in touch with for ideas and info about things I could try out here – Bob, Josiah, Jon E. and Drake especially.

We all busted it in the garden to get beds double dug and amended with compost, manure, biochar etc. Here are my main two guys momodou and modou charging it, 5pm heat and still an hour of work to do. Gambians will put you to shame with their ability to work! All the baby vitamins I ate growing up, fluoride toothpaste and green leaf veggies and I still couldn’t hold a candle to a Gambian with none of that stuff in their history. Love these guys, even in Ramadan, fasting from food and water all day, many will still work a hard morning. It’s amazing. These people are tough! And that makes me………..um?………….still learning to be tough, and that’s the truth! My host mom used to laugh when I got sick and say “Mohammad, your body doesn’t know work!” Ha, she was right!

In the spirit of the “Ag Lab” garden we have another day of strange stuff going on: IMO in the foreground cooking and biochar in the background. And if you look far back on the left, under the baobab tree you can see the farm crew visiting with a teacher that came by. If you haven’t guessed already, they’re definitely brewing attaya. When the biocahr takes 4-5hours you gotta pass the time somehow.

This is how the garden looked when I first arrived.

And after a couple months this is how the garden looked. If i could go back and do it again i’d have made 25% of the amount of garden beds and just focused on doing a really good job with those. Instead I saw all the space and wanted to fill it up and take advantage of the fact that I had water and people to help me. This was a mistake though because just to water the beds twice a day, some 96 of them planted at times, took way too much labor time, and our water came from a slow flowing hose. So this was an important farm and life lesson. I learned that it’s very easy and emotionally fun to start projects, seeds, cuttings but it’s really tough to maintain all that and stay diligent throughout the entire life of the plant. I love the idea of fresh carrots much more than the day to day grind of watering them. 90 or so days, twice a day, in scorching heat, plus weeding, all for carrots!? shoot, lets just buy the damn carrots! lol, that’s the point you get to. And as I start to farm here in the states I’m seeing that it’s things like compromise, restraint, good planning and self awareness that’ll sustain a farm, idea, relationship. It’s another instance in Gambia where I thought i’d go out to help and teach but really it was me who was given the lesson.

I’d not thought too much of this hole upon first glance. It’s just a hole right!? It was originally dug by students to make pit compost. But, as things do, it changed function for me after two events: 1. i’d watched a permaculture video where a story was told about burying a horse under a grape vine, and 2. my counterpart said he had thrown a dead pig out in the bush. Although the pig had been in the sun for a day I went and grabbed it and put it in this hole, burying it with lots of IMO, biochar and compost. 50lbs of organic matter instantly added; but my thought was how long would it take to break down and be ok for plants and trees to sink their roots into? The stinking, maggoty, bloated and baked pig was probably one of the grossest things i’d moved around and I really felt bad because I wheeled it past modou as he was praying! Ah, he said no problem though.

This is my little host brother Mustafa. We planted this mango together in an old bakers yeast bag. Mustafa had a dog named “sobie” and always called me for lunch when it was ready, saying “Mohammmad??? Kontongo….” This guy is seriously handsome and really brave, going beekeeping with me at the school once. Since I was the youngest sibling in my family I really enjoyed having a little brother for a couple years, someone who looked up to me and would tag along with me to play hacky sack, ride my bike or go get a soda.

Naming ceremonies were one type of event you were often invited too and it was kind of an honor to hold the new baby. Usually a naming ceremony would happen about a week after the child was born.

Language instruction. Peace Corps would reimburse you if you took language lessons with a local teacher. Learning the language is important for all aspects of service. Sure I could use Mandinka to talk with other Gambians, go to the market etc but the best part of knowing the language is when it allowed me to become part of the scene – a joke, a naming ceremony or just a chat under a mango tree about stars. Mandinka language is so dear to me and I still find myself thinking it and speaking it aloud when I’m working. I rented the DVD Roots the other day and it’s nice to be able to understand the Mandinka in that. And it’s deep too, with proverbs and specific vocab words or concepts I’d not heard of until i arrived in Gambia. E.g., there’s a specific word to use to describe when someone rushes off from a meal such as lunch or dinner and then forgets something like their keys and has to come back into the room to grab them. I just did this yesterday with my hat, leaving it on a friends chair and having to go back and grab it. In mandinka you would say this certain word when they come back in the room, i like that. Ask me to speak or teach you some Mandinka if you see me around.

Metal work! This is my metal fabrication and welding guru Ma Janha! This guy is great and was so patient with teaching me about welding and metal fab. Here we are in the schools metal shop where he worked during the day. We just finished making those book ends on the table. At night he went to his own metal shop and worked on whatever jobs the people of Farafenni needed done. Ma was so smart and just cracked me up because he was so calm all the time and dressed like a 70s surfer with cool boat shoes and slacks, riding around on a maroon sport bike. How many times was I welding and making an absolute mess of things, welding in the wrong spot because i’d blinded myself with the arc or just burning holes in all the metal from being heavy handed!? And he would just say calmly, “oooooh, nooo, Stephen, that’s not the way…..You gotta do it real light. Easy easy…” 🙂

I’d learned to use a grinding wheel at the welding shops in Farafenni. One of my favorite items in the shop was that anvil bolted to a big tree trunk in the background. I’m not at the skill level i’d like to be with metal but I think over the next few years I can keep hammering over an anvil, buy a lil buzz box, and get to where I want to be.

This was one of the first welding projects I did at the shop with the guys. These are jibida holders, the jibida being a large clay pot used for holding water. My host mother fatou guessed that they were holders for drums. Drinking water and drumming are both really important in Gambia :). I would make a few of these for fellow PCVs in the months to come; the best part is to make the top ring, taking a straight rod and beating it with a hammer into a near perfect circle.

This is Ma’s shop in town and a place where I had a lot of fun, taking a break from being a farmer to be a welding PCV. I spent this day at the shop with forearms burning from all the hacksaw work to cut these pieces. For some reason it was always a struggle to find a sharp hacksaw blade, so you kinda had to grudge through the metal with a dull blade. Ha, when i think about it, Gambians are so smart, that the guys probably just waited until I couldn’t take it anymore and would give them 50 dalasi to go buy a new blade! When you’re new at the welding shop, as I was, you don’t have much skill so you’re given simple jobs, one of them being simple cutting with the hacksaw. As you try other jobs and gain more skill you work your way up the ranks.

More hacksaw work at Ma’s shop, with his little brother supervising my first attempt at mitre cuts for a farm tool handle. In Gambia certain professions stayed within the families, and the janha’s were shopkeepers and welders, with 4 generations of them doing metal work and having several shops in Gambia. So I was in good hands with these guys. Plus, they were always very patient with me and let me make all kinds of strange things there.

One unique practice I learned in Gambia at the shop was how to cut metal with a hammer and chisel. It was slow but rewarding when you finished. We would have 3-4 chisels laying around the shop and undoubtedly one of them was the sharpest and best so we’d try to grab that one. This sheet metal was relatively easy to cut. Working in the dirt with metal is a fond memory for me; sparks flying and attaya brewing.

I believe my mother sent me this PEACE pin. It was put on my bag and I found that putting a peace pin on your backpack is a lot easier than going out and making peace. One great thing is that the mission of peace corps is “world peace and friendship” and that’s something I can get on board with. And putting the pin on the bag is a good start if nothing else. How do you best help and how can you make peace are questions i’m still wondering about and encourage others to think about.

This picture was from my original “fail blog.” We had set this catcher box up in a tree to catch bees that we would later transfer into a full size hive. When i came back to check it a few days later I’d found that someone had thrown a rock at it, knocking off all the top bars and scaring the bees from it in the process. After building, painting, baiting and hanging the box, catching bees and thinking you got it all set, to have the rock thrown at it, likely by a student for a quick laugh or dare, is a real drag. I think maybe it highlights my assumptions and expectations (i.e. someone wouldn’t just destroy this box, i’m here to help and learn and with that intention nothing bad will happen, people respect what i’m doing and will show that through their actions), and those both got a reality check during my service. I’m laughing now, detached, thinking the kids were probably prodding each other on yelling “smash the toubabs bee box!” lol, well ya can’t blame em for raging I guess!

Care packages. You hear about care packages before you get to country but don’t really understand how valuable they are until a few months at permanent site. Not only are they tasty and nutritious but they also are familiar and remind you of your home and the people there that are supporting you. The drink mix to add some flavor to plain water, the books to give you a mental health day where you can read and do nothing, the beef jerky for protein and the powder for heat rash and swamp foot. Sure the packages would take 2 months to get to you but they were a real godsend. My people in the states sent me lots of packages so I was really lucky! If you made it to the capital, Banjul, you could check the mail room at the main PC office and pickup your mail before “mail run” would happen. Near the end of my service I started opening my gift boxes with my host family and it was a great cross cultural activity to share the items and explain things seen in US magazines.

Ahhhhhh! Stephanie, i could’ve killed you for all this stupid glitter you packed in there lol! But, as always, Steph, my sister, does things with style and has a great sense of humor so this ended up being one of my favorite care package items, and i love the note she wrote on there too. Family support was a big help for me and everybody really came through for me. I always had a letter, an email, a gift box or a comment on this blog to encourage me.

About 1 year into my service the neck of my guitar broke. I used to compulsively bend my neck from stress and I found that in Gambia I stopped doing this for some reason. This became the model for how I wanted to live my life post peace corps; simple, nature filled, low stress, full of books and music, in the environment with friends doing service instead of thinking and talking about what I value until i could do it for a few hours on the weekend. I wanted to live the PC lifestyle post PC to the greatest extent possible and I’ve made choices to try to do that.

This man stole my beekeeping boots! Ha, and I’m kind of proud of him for doing so in a strange way, it’s funny to me all the times he said “I haven’t seen them” and then my counterpart saw them in his house! We all shared a meal there together a few days later and then I think I even saw them! But what are ya gonna do, call him out while your a guest in his house? In Gambia there’s a little joke that older Fula men (Fula is one of the main tribes in Gambia) are always carrying a bag for some reason and it’s definitely true here. What is in the bag mister!?

Some bantabas (outdoor sitting places) are made from sticks and covered with leaves and grass to provide shade. One day the mango on the left will be big enough to shade the whole bantaba. I was lucky to be invited to this village by Modou; his mother lives here so we rode our bikes here a couple times a year to visit her and catch up with his relatives. It was a village right next to the Gambia river and about 6 miles away from my house in Farafenni. Whenever you travel or visit someone it’s the custom to bring “silifando” which is a small gift from the road; we brought attaya tea and the woman sitting on the bantaba is brewing it.

Modou and I get ready to spend the day at his mother’s village. Gambian hospitality is such that two chairs are brought out for us, placed in the shade, attaya is brewed, hand fans are provided and we sit and talk until lunch time. It’s hard to imagine but we sat here for the next 6 hours. Even I can’t remember what we were doing the whole time. People come by and visit and greet you, you eat, you talk and then you brew attaya again perhaps and then the sun was setting and we rode home.

One month before I was due to leave country I returned to my training village, Kaiaf, to catch up with my training family and get this picture with my host father Musa. I gave Musa a copy of the farming book I wrote and spent the day with my people there. It was nice to be back in Kaiaf, i felt like a son that had moved to another town and finally returned to a proud family. I spoke Mandinka much better, had lots of stories, had farmed and really felt sad that I would be leaving. While I was away Musa and the family had hosted 3 other volunteers and had a new baby, which they named casey after another PCV. It was sad to say goodbye to Musa, as he gave me my name and was my first father figure in Gambia, and I was also the first volunteer he ever hosted. Although I was encouraged to change my name when I moved to permanent site, I kept the surname “Gassama” in honor of Musa and the name he provided during the naming ceremony. Names are important in Gambia and my loyalty to him and the impression my first family made on me warranted me keeping the Gassama name.

Two things that are great and stick out to me in this photo – the gambian ingenuity of brewing attaya on a stove made from an old tomato paste pot and using that black flipflop on the ground to fan the coals. Second, the shoes modou (on the left) wore to work on the farm. Classic style there and modou owning it and somehow pulling it off like it’s no big deal! lol I know modou didn’t think about it at all but man we really had a laugh about his shoes.

The mason was able to add another couple layers of blocks to my wall and give me a little bit more privacy from the street. This is the porch in front of my house, where many of bean sandwiches and nescafes were consumed. See that jumble of wires in the upper left of the photo – that’s the electricity meter, connected to larger wires on poles and eventually to a generator near the center of town. We had electricity at night and in the morning in Farafenni and when I left they were working on building a new generator that would provide power 24/7. There was actually a part of me that was disappointed that I had part time electricity as I’d fantasized about being in a bush village, in a grass hut, mastering the local language, reading 200 books, writing a novel and having a spiritual epiphany brought by harsh living conditions and simplicity. Instead I did half of all that, made some great beats on my laptop, wrote a farming manual and caught lots of cold drinks and movie nights with my people. It was perfect how it ended up.

My friend Grigor sends me his “templar” book, and a fresh 20 to use as a book mark! Grigor held down the homefront, taking care of the farm and my dog frida while I was away. Ok so the 20spot, toubab money, hey it’s very powerful! If I had USD I would take it to the Lebanese guys who owned the supermarket in town and they would convert it into Gambian Dalasi for me. When I was there the conversion was about 40 dalasi for each dollar. I was given a stipend of about $160 dollars a month so $20 was a good increase.

At the start of my service this is what our tree nursery looked like.

More trees are added to the nursery. Eventually we had something like 400 trees or plants in here. Again, easy to sow seeds and brag about large stock numbers, difficult to outplant and maintain all of them.

Here’s the nursery at its later stages, getting a little packed with lots of trees. When we would host garden trainings at the farm we’d say “and everybody gets a free cashew tree to take home and plant!” just trying to get these trees outta here!

Make compost, that’s the mission. If nothing else I think I helped a lot of people realize the benefit of piling up a bunch of different material as a technique for improving the soil. Did i tell Gambians about 30:1 carbon:nitrogen ratios and the ultra fast berkeley method? Not really. Mostly i told them to pile all the stuff they usually burnt and just leave it. Flip it if you want to or have the energy, or add manure and water too it if possible. My favorite thing was to dig a hole in the piles and have Gambians put their hands inside to feel the heat. This was a real mind blower for farmers who have never felt how hot a compost pile can get. One teacher even said “I will never burn my field again, and will make compost every year. It really helps the crops.”

This is the video club! Anytime in the day I could grab a sandwich and a cold drink and go watch a football game. I was lucky to live in a bigger town, and could even get a beer. At times, like for the world cup, the televisions were running off a generator. One of the hottest times I’d experienced was in this room with 120 people, standing room only, watching a world cup game.

On this day I was dropped off at my new house in Farafenni! With two trunks and a bike and a few bags you start your site visit – the time where you get a few days to see your permanent site. My house was huge! Most PCVs houses/huts were half the size of my front room alone, and i also had two back rooms. I had a large front porch and a back with a shower. I got really lucky with my site placement. I later talked with my training team and asked them why they put me there and they said that they knew the large town of Farafenni would be challenging for many PCVs but they thought me being a guy (this would make me safer and be hassled less), a little bit older, and having the right counterpart and school farm setting would be a good match. I’m so grateful I ended up in Farafenni, it was perfect for me. Thousands of people, manic excitement and attention, fried chicken and cold soda, huge garden and farm, beer, tourist bird watchers, welding sparks, christian raised pork, trans africa rallies, runaway goats, and a tall white guy from michigan now called mohammad in the mix of it all, scrapping it out! Yea, bring it on i say! I handled it all and really rocked it!

2 years 2 months under a bug net. I’m so appreciative now that i don’t have to crawl in and out of bed under these things anymore. I feel so free in bed and uncaged. The net is a little claustrophobic but you get used to it. One thing to watch out for with these nets is that when their really new the treatment on them is so strong that it’ll make your eyes and your face burn. Some PCVs woke up in the middle of the night with a burning face and ran to the bathroom to try wash away the burn. Word to the wise – air out that bug net before you sleep under it. I’m just really happy I don’t have to sleep under these things anymore. And believe it or not, that mauna kea hoody on the door was worn quite often – most nights on the bantaba and during rainy season.

I had to put this picture in here because it’s not a poised cool guy shot like some of my other ones and it really captures something. In the accidental picture taken here i think you see the state of sweating and general tiredness and slight confusion that was my normal mode of operations. And i’m on a huge ferry floating across the river Gambia. I’m probably thinking what am i doing out here, on that big dumb blue boat lol, and why for so long!? honestly you get to a point where you catch yourself thinking “geez louise, what am i doing here!” and then right at that moment some little kid yells “toubab! give me your bottle!” lol and it all works and makes you laugh because it’s so ridiculous. It’s a well known fact amongst PCVs that in a single day, perhaps single afternoon, you can cry laughing about a story with your host family, actually cry out of frustration and confusion and then possibly tear up because perhaps you saw how special what your doing is. The rapid change of situations and emotions can be extremely fast – from the bottom of your range all the way to the top in a moment. Gambia is pushy and it’s so good for you.

A piece of bamboo holds up the wick as beeswax is poured in to make a candle. When the wax solidifies we cut the tape that’s holding the bamboo halves together and have a candle. Simple good and smart.

This is one of my favorite pictures because it captures what peace corps is really like to some extent. The PC guys in DC would never run this in one of their pamphlets they use to recruit people but this is what a lot of the times are like – silly, fun, educational and eh just trying our best to help. In this picture it’s after lunch at our beekeeping training and one PCV is yawning tired, next to him one of the Gambian instructors is actually sleeping, and in the foreground our PCV friend from Guinea has put the block of beeswax we were passing around on his head! It’s all so perfect and real. I think that’s what I learned from my service and travel, that underneath all situations there’s a funny and uniquely human side of life that’s really enjoyable and special. It’s the joke made when the interview is over, or the exhausted laugh when everything well planned falls apart. Peace corps is really great and special, but not for the reasons you guess it will be before you get in country. I didn’t imagine I’d be in this situation before leaving but it’s a real gem to me now :).

My host grandmother, tala, shows me who’s boss and unknowingly makes this picture so much better! This is my host family in Kaiaf, my hosts for the 2-month pre-service training, grandmother out front, daughter behind in the white tank top and granddaughter to the left in the yellow, along with adopted grandson in the black t-shirt.

My host father Musa went to the fields this day and brings me back a bunch of groundnut (i.e. peanuts). When he walked in my hut and held these up I was thinking “what is that!?” I’d not really known how or where groundnuts grew until I came to Gambia. I’m ending with this picture because it represents the best part of my service and time in Gambia; the simple lifestyle with others and nature that leads to connection. That’s it. Connection was the point of my time there and that’s what happened.

Stay tuned for future posts…..and thank you for sharing the journey and sticking with me. -stephen